Factory Farms in the Flood Zone: A Farm Forward Interview

Since Hurricane Florence hit eastern North Carolina in September, more than three dozen hog lagoons have breached or been submerged, releasing millions of gallons of toxic hog waste from CAFOs (Confined Animal Feeding Operations) into the surrounding ecosystems. As floodwaters carried waste from the lagoons into rivers, streams, and the groundwater, they threatened the health of people living in the region and caused immeasurable and possibly permanent harm to ecosystems. At least 5,500 pigs and 3.4 million chickens were reported killed due to Hurricane Florence, according to preliminary estimates from the North Carolina Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services, but the true numbers could be much higher. This catastrophic harm to animals, humans, and the environment was not only preventable, but also predicted.

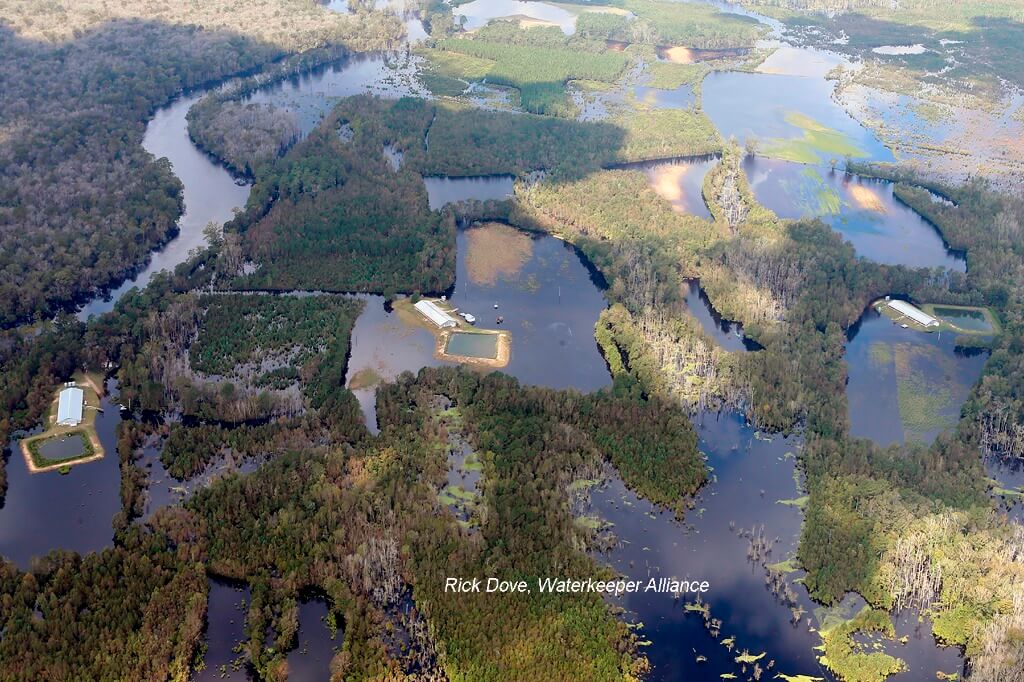

Hurricane season has barely ended in North Carolina, and yet national attention to this environmental and moral disaster receded with Florence’s floodwaters. We interviewed Rick Dove and Larry Baldwin of the Waterkeeper Alliance and Jessica Culpepper of Public Justice to learn why it is so hard to remove CAFOs from flood-prone regions and to ask what people can do to help. Rick and Larry took all the photographs in this article as they flew over Eastern North Carolina in the week following the storm. The interviews are below. First, some context.

Last September we spent a few days with Rick and Larry in Telluride, Colorado, during the premiere of the documentary film, Eating Animals. The film lifts up Rick’s and Larry’s efforts to monitor and expose the devastating damage that swine CAFO runoff has caused to river ecosystems in North Carolina. They told us how—despite advocates raising awareness about the problem for decades—politicians have made few moves to relocate or shut down the CAFOs, or to prevent new ones from locating in flood-prone regions. That weekend a storm warning was in effect for North Carolina, and Rick and Larry worried aloud that severe rains might flood the CAFOs, as several previous hurricanes had, polluting the rivers and lands that they had spent decades protecting. A year later, their worst fears have come true again.

Rick Dove, of the Waterkeeper Alliance, regularly flies Eastern North Carolina to monitor pollution from hog facilities. This photo shows a CAFO with a breached lagoon spilling its contents. The unflooded lagoon on the left displays a characteristic pink color, caused by the mixture of chemicals, bacteria and hog waste. Photo courtesy of Rick Dove

The post-Florence ecological disaster is not a freak accident, but (literally and figuratively) a spillover into public view of the systemic harms to animals, humans, and the environment that the factory farm industry normally keeps hidden from sight.

Because the government agencies tasked with monitoring factory farm conditions provide very little actual oversight, investigations by activists are among the only effective ways to hold companies accountable. But in 2015 North Carolina became the eighth state to pass an ag-gag law, legislation that impedes activists like Rick and Larry. Ag-gag laws are designed to hinder investigations of abusive or environmentally dangerous conditions on factory farms by prohibiting, among other things, any individual or public interest group videotaping the farms themselves.

According to Farm Forward’s General Counsel Michael McFadden, who has spearheaded our own anti-ag-gag efforts,

The citizens of North Carolina face two problems—hog feces and hurricanes—and both are likely to continue getting worse over time. But rather than call out and address the increasing risks of keeping millions of animals and tens of millions of tons of toxic liquid waste hidden from public sight, North Carolina’s legislature chose to bury its head in the sand when it passed its ag-gag law in 2015. The law allows companies to sue their employees for exposing abuse, including punitive damages of up to $5,000 per day. While the law was clearly intended to intimidate animal advocates, it’s written so broadly that it could be used to punish whistleblowing at hospitals, nursing homes, and daycare centers.

— Michael McFadden, Esq.

Since Hurricane Florence, Rick and Larry have been flying over the floodplains documenting the flooded barns and breached and submerged lagoons while Riverkeepers in the state have carefully tested water for contamination. They share the photographs and information they collect with the media and with groups that work to get CAFOs removed from flood-prone regions. One such group is Public Justice, which uses the data that Rick and Larry collect in lawsuits against the largest animal agriculture companies operating in North Carolina.

We spoke with Rick and Larry, and with Jessica Culpepper, the Food Project Attorney at Public Justice, to ask them what people need to know about these images showing flooded and damaged CAFOs in the aftermath of Hurricane Florence.

What follows are excerpts from those interviews:

Farm Forward: Can you help us Understand what we’re seeing in these Photographs of flooded CAFO’s and hog lagoons? Do any images stand out for you?

Rick Dove: Since 1993, I’ve got over three thousand hours in the air, flying over these factory farms. In the 11–12 days after Hurricane Florence, I spent 30 hours in the air. So I’ve seen it again and again. The [images] that stand out most in my mind are where the berms of the lagoon completely blew out, and all the contents, an estimated seven million gallons, went flowing down the river.

We’ve seen a lot of these facilities where…the industry calls it “overtopping.” That kind of sounds like putting whipped cream on a dessert. “Submersion” is what’s happening. These lagoons go underwater, and when the floodwaters recede, they take the contents with them. We’ve got videos of hogs floating down the river. We’ve got dead chickens floating around in their own feces. Some journalists actually kayaked inside of some the poultry barns and filmed the dead chickens floating in the barns in the muck. It’s a terrible sight.

The industry term “overtopping” refers to floodwaters submerging hog lagoons, sometimes causing even more contamination than breaches. Lagoons that have been mixed with floodwaters appear brown, instead of their characteristic bright pink color. Photo courtesy of Larry Baldwin.

Farm Forward: Why does this keep happening?

Jessica Culpepper: The answer is not to rebuild safer, because there is no safer. Even if you could prevent water from inundating the facility, there’s no way that operators can get there. It’s either leave the animals there, or rush them off to slaughter beforehand, which usually means [transporting them to] farther slaughterhouses—that is incredibly stressful for the animals. These facilities should never have been built there. If it were up to me, Smithfield would clean up its own mess, and it wouldn’t be the taxpayers buying out these facilities. But I think it’s more important for the public to use its resources to make sure this never happens again. In the 100-year floodplain, there are 62 hog facilities (over 200,000 hogs), and 30 poultry facilities (1.8 million chickens)…The worst possible thing that could happen right now is any kind of move to rebuild. I don’t think there should be CAFOs. But certainly, we should not be raising them in floodplains.

Rick Dove: The hog industry has taken the same approach for the past 25 years … This is how it goes: First, everybody gets very concerned because a hurricane is coming, and for good reason. The hog industry says, “We’re getting prepared,” but there’s nothing they can really do to prepare. They could move some animals, but some is the key word—they don’t have the ability to move them all, there’s no space for them. They don’t know what areas will flood until the hurricane arrives. And there’s no way they can get these lagoons out of harm’s way. And then everybody gets concerned about it, there’s a lot of news. And [after the storm] everybody says, “Now we’re going to fix it.” But soon the aftermath of the storm fades away from memory and the press quits covering it. Then they start repairing the buildings and putting the animals back in the same buildings. Until the next hurricane comes, and then we do it all over again, and again, and again, and nothing really changes.

Larry Baldwin: We were no better prepared for Florence than we were for Floyd in 1999 … we still have too many of these facilities in the 100-year floodplain and the 500-year floodplain. We’ve had three “100-year” floods in less than 100 years. Now, three times we’ve proven that these facilities should not be located where they are. What are we going to do?

Poultry barns in North Carolina during the flooding from Hurricane Florence. Photo courtesy of Rick Dove.

Farm Forward: What kinds of legal actions are being taken to prevent this from happening again the next timer there’s a big storm?

Jessica: In the aftermath of Floyd, in 1999, the state legislature started the North Carolina Swine Flood Buyout program. To date it has bought out 43 swine operations that were in the 100-year floodplain…When they buy out these facilities they put a conservation easement on the land that says no animal facilities can be located there. That is a surefire way to make animals safe from flooding and people safe from the raw sewage.

Rick: The river’s edge is no place for these facilities to be located … What’s worse, all these new poultry facilities are being built right in the same place. What amazes me more than anything is—with all the problems faced by the older swine and poultry facilities located along the rivers—they should know not to build new poultry facilities there. But land in the lowlands is cheap, so that’s where they build them, and now they’re getting flooded too. They keep doing the same thing over and over again expecting a different result, and that’s never going happen.

I think if anything’s going to change it, it will be these lawsuits with these horrific punitive damages. There are only three cases tried so far, with some 21 more to go. If these cases keep coming in the way they have been, it’ll be a terrible blow to this industry. Everybody says, “Now change is going to happen.” From my standpoint, I say, “We’ll see.” I’m not overly optimistic. I’ve been through this drill so many times.

Despite environmental warnings, swine facilities (and, increasingly, poultry facilities) continue to build in flood-prone areas where they oftentimes contaminate waterways after heavy storms. Photo courtesy of Rick Dove.

Farm Forward: What can consumers do?

Rick: The public has got to say “We don’t want this anymore.” Groups out there are talking about boycotting the meat, they’ve got yard signs, so that’s already happening. Personally, I think we make a big mistake in eating as much meat as we do. I don’t eat any. I was a vegetarian for years. I’m now a vegan. I’ve found a plant diet that for me is very, very satisfying, and very, very good tasting and healthy. I don’t miss meat anymore. That’s a personal choice I made—I don’t tell anybody else what to eat. But if all of us relied less on meat, it would be better for the planet, better for our health, and it would scale back a lot of this pollution that we’re seeing from these factory farms. If we’re eating the products that come from farming, we’re participating in farming activity … We’re all farmers and we have a duty to have a say in how food is grown.

Larry: It’s going to take the public … to be the ones that force that change. As long as we keep buying the bacon from the Smithfield Foods or the industry leaders, we’re still part of the problem.

Farm Forward: Is there anything that you think the media hasn’t paid enough attention to in the aftermath of Hurricane Florence?

Rick: There’s one issue that hasn’t been covered as much as it should…and that is what happens to all these dead animals. First of all, we’ll never know from the industry exactly how many of these animals perished…But the one thing I do know, there is no efficient way of disposing of these huge numbers of dead carcasses. And there’s a safety concern connected to that. In North Carolina, under normal conditions dead hogs are taken to a rendering factory, they’re boiled down for their fat and so on. But when we have a hurricane, or we have a disease like PED [Porcine Epidemic Diarrhea] which just killed millions of animals in North Carolina, the only way to get rid of them is to dig a hole in the ground and bury them.

In many instances where we’ve seen these burials take place, they’re unsupervised—the location is chosen by the local grower, there’s no chemicals or anything put in with the animals. In many cases they’re left uncovered for weeks. Buzzards are seen feeding on them. There’s groundwater in the burial pits mixing in with the dead carcasses…And the only agency in North Carolina that has supervisory control is the Department of Agriculture and its veterinarian service, but to my knowledge they don’t do any supervision.

We’re photographing it from the air and the ground when we can, and we’re sending them the pictures when it happens, but basically, they take a hands-off attitude … We have asked for years that the government task the local county health director with the ability to go in and supervise these burials as a public health issue. But to the surprise of most citizens, no county health director has any authority, under any normal condition, to go into factory farm buildings and do a health inspection. The only health inspection that is done is by the state veterinarian, and to my knowledge it’s just not happening. So, there is very little done regarding the protection of human health as the result of these animal deaths that occur.

Larry: This is. . . life and death stuff down here, not just for the animals, but for the people as well. Out here it’s environmental justice issues: the waters around [the CAFOs] are contaminated. If you happen to get your drinking water from a well…We know people are getting sick, we don’t know exactly why. We’re exposing communities to a level of health impact that we don’t know how to quantify.

Jessica: I would like to see the North Carolina Swine Plain Flood Buyout Program extended to poultry facilities. [Four] million birds have died. It’s really tragic. Unfortunately, the existing state program is heavily defined [as applicable only to swine]. Legislation needs to get together with industry and change that. In the time between Floyd and now, there’s been a really heavy influx of concentrated industrial poultry operations. And the laws need to catch up with that.

Photo courtesy of Larry Baldwin.

Farm Forward: What about the farmers, the contract CAFO owners? Are you seeing any of them question this system?

Larry: They’re corporate farms…I’m sure these producers are not getting paid by Smithfield when they’re not producing. I have compassion for these producers…they’ve bought into a system that was broken from the very beginning. There are some out there—who obviously do not want to be identified—who will say completely off the record, “If I had this to do again, I would never get into this situation.”

Jessica: Smithfield and the industries knew this would happen…they had a responsibility to their contract growers to make sure that they were located in a place that would keep their animals safe. That said, the important thing to me right now is getting these facilities out of the 100-year floodplain.

Farm Forward: For people who want to do something to help, right now, what do they do?

Rick: It’s very helpful for the public to support environmental groups generally. You need to look at the reputation of each group—how they spend their money, what they do, what is the return for the money that people donate…So, certainly, Waterkeeper Alliance is an organization I’ve been associated with for over 25 years. To me they are at the top when it comes to water protection. But there are other organizations out there as well. Farm Forward is certainly right up there at the top as well. But people need to get involved, and they need to not only contribute money, but actually get in there and find how they can join up with the organization and volunteer and do good work.

Larry: I don’t care whether you live in North Carolina or don’t live in North Carolina. You can contact your own senator, or call the senators in North Carolina, [or the North Carolina county officials who] are in the pocket of the industry and will try to keep things as status quo as much as they can. Support North Carolina Waterkeepers so they can do more on-the-ground sampling before, during, and after the storm comes through.

In Closing

Rick, Larry, and Jessica know that media attention to the problems of CAFOs was drawn by Hurricane Florence and has faded after the storm. Sustained attention will be required, however, to put pressure on politicians, government agencies, and companies who could prevent North Carolina’s destroyed CAFOs from being rebuilt as soon as the floodwaters subside. There is only one solution that permanently addresses all the harms of factory farming that Florence has brought to the surface. We must end factory farming as a means of producing our food. A food production system that values cheap meat products more than the health of people, the lives of animals, and the well-being of rivers and other ecosystems should not be acceptable to any of us.

Here are a few ways you can help right now:

- Support organizations that provide the oversight of CAFOs that the government is failing to deliver. You can donate to Waterkeepers Carolina, or support the Waterkeeper in your specific watershed.

- Don’t buy products from factory farms, and tell your institutions to stop too. Farm Forward has resources to help you understand animal welfare certifications, as well as tools to help institutions like universities and businesses make the switch to “less and better” meat.

- Join us in ending factory farming. It’s the only long-term solution to ensure that this sort of harm to animals, people, and ecosystems does not happen again.